Purpose: Feature on homophobia in sports for Express, New Zealand’s LGBTQ+ news outlet

My role: Executive editor (feature writing)

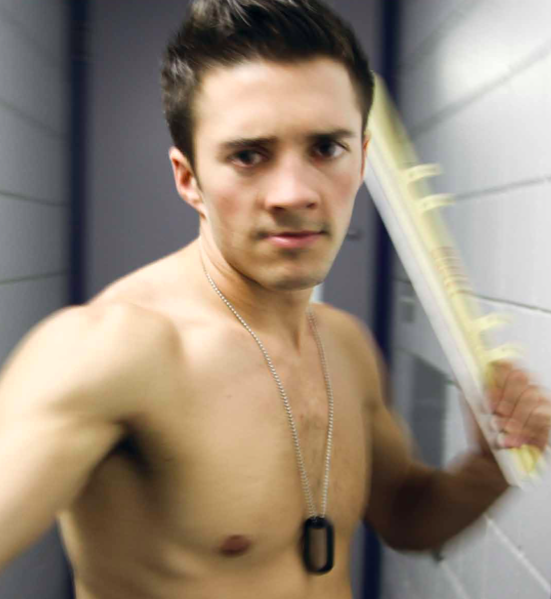

Olympian Blake Sjkellerup

You may be aware that there’s this big, international sporting competition in New Zealand right now: The Rugby World Cup. They’ve got all kinds of people out on the field – white, brown, tall, squat, bearded, shaved, muscly, lean... but there’s one thing that’s missing among the diverse faces: an out gay player.

Why is sport – in particular our national sport – still a place where homophobia persists? Why does the stereotype of the gay “sissy” still exist? And what can we do to combat this? Hannah JV caught up with a range of LGBTQ+ people in sport to find out how to climb to the top of the ruck and stand proud as an out sportsperson.

Go your own way

Patricia Nell Warren is a hardy woman. A pioneering feminist in 1960s America and then a pioneering out lesbian in sport, she’s had her fair share of hills to climb over the years. But she’s living proof that if you stand up for what you believe in and are confident in who you are, change can be achieved.

On the phone from her American office, the 75-year-old writer says, “I was involved in running in the late 1960s when women were trying to get recognised and treated fairly in long distance running. Back then, women could not run further than 2.5 miles in sanctioned events. We had a huge political struggle for recognition.”

Then-closeted Warren had met a number of lesbians through her work for women’s rights and decided to combine her passion for running, the struggle for women’s recognition and a number of lesbian characters to write her novel The Front Runner.

“I started out as a feminist and I think my activism as a woman meant I could be more courageous about coming out. In 1973 it was time for me to stop pretending – I wrote the book and then in 1974, when the book was released, and I couldn’t pretend any more and came out.”

The book was extremely controversial at its time of release, but has had a lasting positive effect on LGBTQ+ people worldwide. Front Runner groups began to pop up anywhere LGBTQ+ people wanted to get together and exercise, and today, more than 100 countries have Front Runner groups.

Around this time we began to hear about young gay men and lesbians getting interested in sport,” says Warren. “Then, shortly after The Front Runner. we had the first big sporting coming out – NFL player David Kopay came out after he left professional football. When he came out, gay liberation really kicked into another gear; that had a huge effect on people.”

Kopay gave up on the NFL in 1972, and since then, you could probably list on a single sheet of paper the number of gay athletes that have come out of the closet. Narrow that down to the number of athletes who have come out whilst still actively playing and that list shortens dramatically. We’ve all heard of Welsh rugby player Gareth Thomas, but even he came out once he hung up his boots for good.

It’s safer in here

What’s keeping LGBTQ+ sportspeople from coming out of the closet? Is it the fear of losing fans? Losing sponsors? Being dropped from the team?

Patricia Warren says, “There is a tremendous amount of homophobia in men’s team sports like football and baseball – these are places that are very difficult for people to come out. I would say the combined circumstances of possible homophobia by your team members, coach, the team’s owner, the fans and of course the sponsors would make it difficult to come out. When you get into lots of money riding on the team, certain people will be unhappy if an out gay man comes along.

“I think it has a lot to do with gender, too. We’ve seen female tennis players coming out but not men. We aren’t seeing the male versions of Billie Jean King or Martina Navratilova; we just haven’t had men coming out at that level.”

A professional rugby player we spoke to wholeheartedly agrees. He’s a Kiwi, he’s gay and he’s happy, but he’s also in the closet. We were lucky enough to speak to him about his reasons for keeping his sexuality a secret, and he said:

“No one in my club knows I’m gay, and in my many years of playing professional rugby, I haven’t met any gay players. I think very few gay guys come out in sport because they fear how they would be perceived and treated after coming out. Rugby is seen to be a staunch, masculine sport – to have a gay man amongst its ranks would somewhat contradict this image.”

Warren agrees that this championing of macho attitudes is keeping a lot of sportspeople in the closet.

“The simple attitudes that prevail in sport say that to be a man, you have to take really huge hits and not let it disturb you; that defines your manliness,” she says. “There’s this perception that all gay guys are powder puffs and don’t like contact, but gay guys can take those hits too!

“But what else is interesting is how on a sport-to-sport basis, the attitudes towards masculinity and achievement differ. At the Athens Olympics, two of the leading male riders in the dressage component of the equestrian section were out gay and there didn’t seem to be uproar like there would be in football, baseball or soccer, and to me, riding and controlling a horse is one of the single most masculine things a man can do!

“Perhaps being part of an individual sport makes a difference. I think in individual sports, you focus on individual achievements. I think to come out you still risk corporate sponsorships, fan base and coaching support, but we’ve seen that to some degree it’s easier to come out in this way.”

I can make it on my own

New Zealand’s own Blake Skjellerup has taught the public a thing or two over the last year. He’s shown New Zealand that he has what it takes to make his country proud at the next Olympics (after he positively wiped the floor with the competition at his most recent nationals comp) and proved that you can be out, gay and in sport while being happy and successful. This concept may not seem revolutionary to some, but as one of the first out gay Olympians, Blake is a trailblazer.

“I knew there weren’t many gay Olympians because when I was coming to terms with my sexuality and trying to find someone to identify with, it was hard to find anyone,” says Blake. “It wasn’t until 2008 – when I read about Australian diver Michael Mitcham – that I found anyone to identify with.

“It wasn’t always an easy time for me to come to terms with my sexuality and to come to terms with it as a sportsman. Not having anybody to identify with was probably the hardest part and it made me feel very alone and isolated. So the main decision was to come out to create an identity and say, ‘Hey, here I am. I’m gay, I’m in sport and that makes absolutely no difference to who I am as an athlete and you can reach the top of your game regardless of your sexuality’.”

Blake admits he was “a little bit naïve” when he told DNA magazine he was out and in sport.

“I thought, because DNA was an Australian magazine, that would be as far as it would go. But very soon after they posted a news brief online, it was quite overwhelming to see how far the article got. I didn’t really expect to see my photo on Queer Thinking at any point in my life!”

Blake never worried about how coming out would affect his sponsors. His reasoning for this was simple – he didn’t have any! ““Mighty Ape has just signed on to help me out, but other than that, I still don’t have any major corporate sponsor. I do know that I have the entire LGBTQ+ community of New Zealand behind me – it’s really amazing to feel that and having their support is great, but at the end of the day it doesn’t pay the bills! “I’m sympathetic to the worry that coming out could lose sponsors. Sport is the number one priority; sexuality is not what defines the athlete. You’ve got to put your sport first, but it’s a sad situation for people who have to hide who they are for the sake of the dollar.”

Friends in low places

Blake admits he knows “multiple people” who are closeted in sport, be it at an amateur or professional level.

“There are a variety of reasons for not coming out, but the common thread is perception,” he says. “They worry about how them coming out will affect their place in the sport. They worry about what the fans will think of them. They worry.”

Out of the closeted sportspeople he knows, Blake says those who are struggling the most are in team sports.

“Teams have to trust each other and rely on each other, whereas for me, it’s all up to me and I don’t have to rely on anyone else.”

Patricia Nell Warren agrees. “I think in individual sports, you focus on individual achievements. I think to come out you still risk corporate sponsorships, fan base and coaching support, but we’ve seen that to some degree it’s easier to come out in this way.”

Blake says, “Team sport, particularly men’s team sports are one of the last surviving places where homophobia is really rife. Perhaps it’s got a lot to do with the spaces they inhabit together. They must still be worried about what they would do with a gay man in their locker room.

“I think the biggest thing to overcome is our own perception of what people think of us. For me, the hardest thing was over- thinking what people’s perceptions were. I don’t necessarily encourage my friends to come out but I do explain how great coming out has been for me. Before I came out, I felt like I had a weight on my shoulders, but once I accepted myself, I felt a lot lighter.”

Blake has become a true spokesperson for the community in the last year – his work with the LGBTQ+ youth organizations of New Zealand has led him on a nationwide tour of schools, where he has spoken out against homophobia and proved the worth of coming out. He also helped spearhead a letter-writing campaign to Prime Minister John Key, urging the government to do something about homophobic bullying in schools. The project was so successful that Blake, along with members of Rainbow Youth and Q-Youth, visited John Key in the Beehive to discuss what can be done to protect LGBTQ+ youth.

“The support I’ve had since I came out, and particularly over the past seven months, has been more than life-changing for me,” says Blake. “I look back on the last year and I’m amazed. I just hope that the work I did turns into something tangible, and that I somehow helped the kids I’ve met along the way.”

A different playing field

Labour MP Louisa Wall knows the feeling of lightness that follows coming out in sport. She says her realisation came after four years of playing in New Zealand’s top netball team, the Silver Ferns.

“I got into the Silver Ferns in 1989 when I was 17 – I was in the squad for four years. When I was 21, I was dropped from the squad began to play rugby.

“There were a lot of lesbians in the Black Ferns when I played but very few in top level netball; I don’t think other than me and a couple of others there have been any. It wasn’t an identity that was well represented, embraced or celebrated, which is kind of the opposite of rugby. I didn’t really enjoy the restrictive nature of netball, whereas rugby was very open and free.

“Rugby – and its real sense of camaraderie and shared purpose – was part of the reason I came out. I was playing rugby for Waitemata and there were two lesbian couples in the team. They took me under their wing and introduced me to the community – it was through that positive expression of lesbianism that I acknowledged within myself that I was a lesbian. From there I led a very honest, open and transparent life. I think the values you learn from playing sport gives people a better foundation to understand what they’re going through and to be proud of it. The foundation of my lesbian identity has been based around my sport.

“To me, netball was quite sterile, and I think that this environment turns a lot of lesbians off from playing it. I’m not saying that we can’t play it – I just don’t think it’s the environment where we can express ourselves.

“I think sport, by definition, encourages you to have a values set, and I think that’s why people move between codes until they find a values set that fits them. For me, I found myself in rugby.”

Take me out to the ball game

Every sportsperson we spoke to agrees that coming out and standing proud are the biggest things a sportsperson can do to lift the shroud of homophobia and ignorance that persists in sport. Patricia Nell Warren says it’s not just about coming out, either – it’s about telling your story.

“If people are given the opportunity to see into the minds and hearts of people who have had to live in the closet and not be true to themselves, their imaginations and sympathies will be engaged. Until these people see the lives of the people they are discriminating against, they’re not going to get it. Stories are really, really important.

“It’s also very important for people who are sympathetic to stand up on behalf of other people. The more people you have supporting coming out, the better. On a team where there has been a lot of homophobia, you only need one person to openly support the idea of someone coming out to create a positive, conducive environment to coming out.”

Blake Skjellerup says, “Positive identification is the way forward – for every negative story we’re set back 10 paces, whereas every positive story seems to only put us forward one. I think we need to change the balance of this and bolster the number of positive stories out there about the community.”

His other big idea is to have a high profile sportsperson throw their weight behind the cause. If you think of the way rugby legend John Kirwan changed the face of depression in New Zealand and fought the stigma that rugbyheads need to be tough, Blake’s got a point.

“I think we need a big name to either come out as gay or come out in absolute support of the community. If we had someone who was really well known to all of New Zealand as the face of a big anti-homophobia campaign, I think we’d see some really big changes.”

Blake’s idea to have change come from the top comes from more than just a public relations standpoint. He also believes in change from the very top – government legislation.

“Personally I’d love to see some anti-homophobia charter with every sport, starting at the top with the Olympic committee. We also need to give the local bodies resources on how to support someone who is gay and wanting to come out in sport. It has to start with positive and supportive management, but it needs to reach everyone.”

Patricia Nell Warren, meanwhile, didn’t stop caring about the LGBTQ+ sporting community after she won her fight to run marathons. Instead, she’s kept up with gay life on the track and field wherever she could. She began documenting historical accounts of LGBTQ+ people in sport for website Outsports in 2002, and after four years of publishing rich and vivid stories, about the likes of Achillies, Joan of Arc and Amelia Earhart, Warren compiled these stories into a book called The Lavender Locker Room.

As for the sportspeople of today, Patricia keeps an eye on everything and notes where inroads towards equality are made.

“They’re making some great progress, and in rugby! In France, the rugby federation has come out against homophobia and a number of French players are supporting this. Even here in the US, where rugby isn’t well known yet, Gareth Thomas coming out had a huge impact – it got people talking.

“I can see there are some cracks in the wall and we’re beginning to get through to people. We will break down those walls of homophobia in sport, but not for a few years yet.”